Ode to the Classics

Motivations

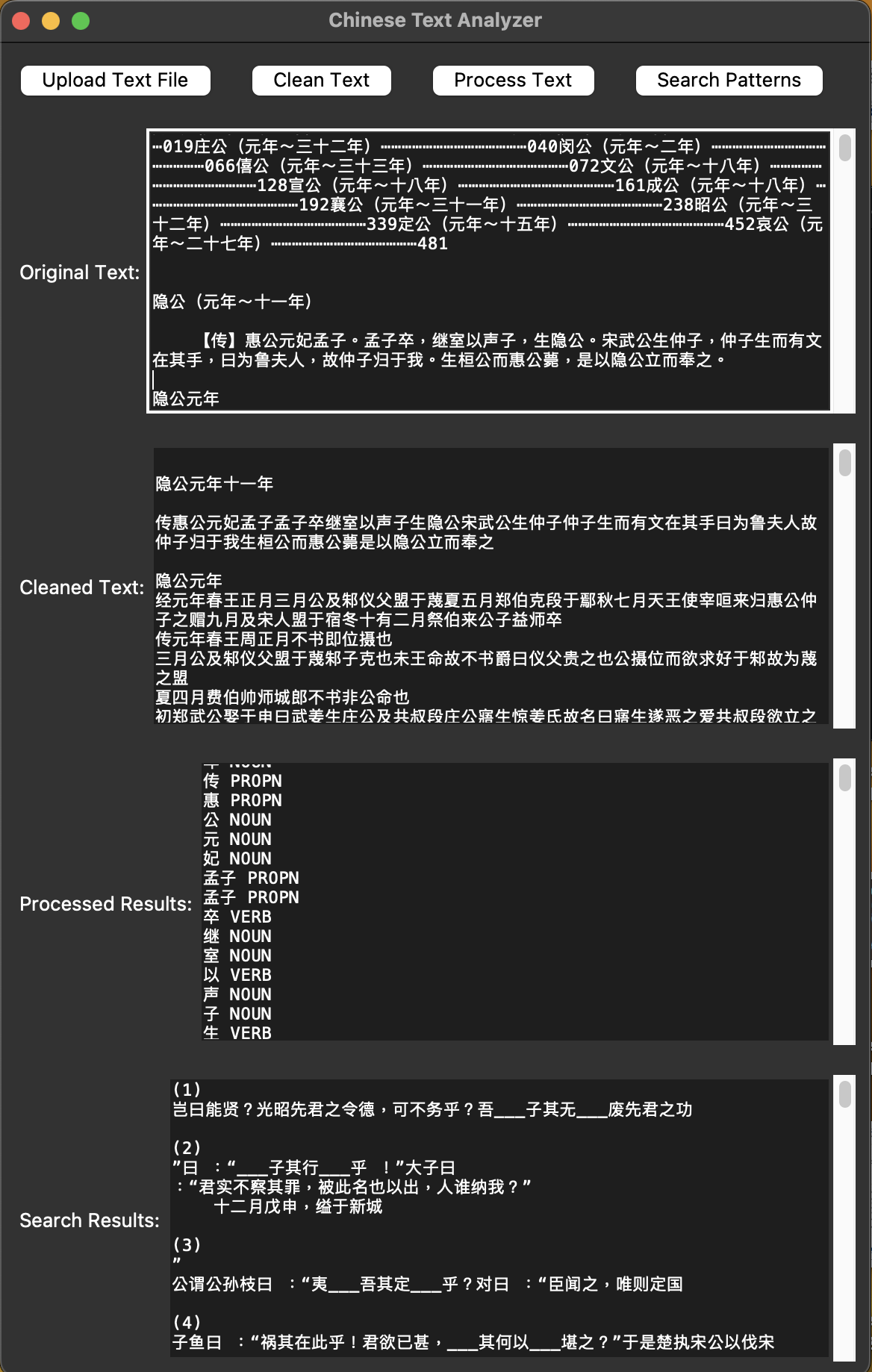

When asked to give my thoughts on characteristics of both Modern and Old Chinese with respect to word order and distribution, it occurred to me that it would be an interesting experiment to see what examples I could find of these phenomena in various Old Chinese texts, especially given the fact that it is difficult to search for this in a traditional linguistic corpus. As we were given an example of how Old Chinese does inflect for case as shown in the Analects in interrogative and negation sentences (e.g., 吾誰欺? and 不我與, respectively), I decided to first look at the Analects and Zuozhuan (similar time period). By using the Natural Language Processing (NLP) toolkit known as Stanza, I was able to identify several similar cases by scanning the text for the same POS patterns.

Findings

SOV in Interrogative Sentences

Looking at the example sentences, I found a few interesting cases that exhibit similar shifts from subject-verb-object to subject-object-verb in the context of an interrogative sentence. These examples were found by filtering out all instances where there was no question mark, which limits our search to cases that are more likely to exhibit grammatical case.

Analects: 其何以, 吾何以, 斯之謂,爾何如 Zuozhuan: 吾其定, 其何以, 吾何以, 其何如, [某某某]将何以, 吾其入 After looking at the other cases in the Analects, it’s most likely the case that 如之何 as a set phrase is throwing off the results, as there is no punctuation after 何, so the primitive search method using POS gives undesirable results, such as:

何其聞, 何其徹, 何其廢, 何其拒 This likely indicates that there is a better method for finding SOV cases.

SOV in Negation Sentences

There were also many more cases of the negative-pronoun-verb pattern. These instances were found by modifying my find_and_highlight_sentences function to only look up the patterns where the first character was either 不 or 未 for simplicity and to narrow down the search to exclude patterns that are highly unlikely to be in a negation sentence.

Analects: 未之見, 未之有, 未之學, 不吾知, 不吾以, 莫予違, 不己知, 不我與 Zuozhuan: 未之闻, 未之服, 未之改, 未女恤, 未之有, 未之治, 未之见, 未是有, 不我知, 不我纳, 不我救, 不吾疾, 不吾叛, 不我与, 不余畀, 不我觌, 不吾远, 不余欺, 不吾废, 不余辟

On the GUI

Exploring how to make a GUI was a useful endeavor as it gave me the time to iron out some of the wrinkles in the original code to make the textual analysis methods in this project more intuitive for someone with no programming experience. It was crucial to allow the user more freedom of control in that they could also include Chinese characters in the patterns along with POS tags, determine whether or not they want to look for questions, and upload texts from anywhere on their computer. It is likely, however, that some of the functions will need require considerable refinement to resolve some potential issues, such as:

-

Will the “Clean Text” cover all cases of all types of punctuation?

-

Will the “Process Text” option take too long to run on extremely large texts?

-

How do I process Modern Chinese texts?

-

Can I upload multiple text files and batch search? If so, there should be indicators on the results for which text the result came from.

-

Can machine learning be applied to search for results and be used to cross-reference the results? If so, how much processing power would that require?

There certainly will be many more questions than this that may arise.

Future Research and Direction

I did not look for other cases of grammatical case within the Analects or Zuozhuan to see how they were tagged. I simply assumed that the best way to find cases of SOV would be a “PRON+PRON+VERB” or “ADV+PRON+VERB”. Next, I could also compare the frequency of certain grammatical patterns across texts from different time periods to highlight certain trends. For example, when do we start to see SOV in interrogative and negation sentences turn into SVO and how quickly does that transition occur? More importantly, I did not consider other methods for identifying the patterns outside of POS tags.

It is possible other methods such as unsupervised or semi-supervised machine learning could be utilized to identify patterns without the rigid framework of some pattern of POS tags. While Stanza does utilize neural networks, it might be useful to engage in some form of feature engineering and run the machine learning models to attach weights to those new features based on context that could perhaps be difficult for a human to see. Specific features that could impact the ability to identify specific patterns are a token’s relative distance in a sentence from other specific tokens, or presence of certain tokens in the sentence where the pattern was found, among others. The semi-supervised approach could involve training the model on annotated data. However, the main disadvantage of this is that the model would fail in more general use cases.

It’s also pertinent to note that the historical context of some of these patterns may be of more use to linguists than simply their POS. It can often be difficult to interpret if the pattern matches that are identified are valid without knowledge of the history of the text. However, I would note that the scope of this project is only in being able to identify the patterns, so that other researchers can find more examples sentences of some linguistic aspect they wish to investigate.

It is entirely possible to turn this entire project into a more intuitive and web-based tool for others interesting in research of Chinese grammar to use. In that case, the users would have all the options of the GUI I have provided, but in a much more accessible format. There are several advantages of doing this: users would not need to download the necessary Python packages to be able to apply these functions; users would not even have to have knowledge of Python or the command shell, which can be challenging for researchers in linguistics; the app developer could collect data from users of the app to refine the app and provide a better user experience and more robust results. This would, of course, take a considerable amount of time to learn how to implement these functions.